|

|

Fujian and Longquan Trade Ceramics in Jepara Shipwreck

During the early 2000s, many celadon and white wares began to surface in the Jakarta antique market. According to sellers, these artifacts came from a wreck located about 34 km offshore from Jepara. Unfortunately, no immediate action was taken by the government to stop the looting. The wreck site was strangely strewn with large boulders. Among the artifacts that surfaced was a stone anchor approximately 2.5 m in length. The authors noted that a similar anchor is displayed at the Maritime Museum in Quanzhou, suggesting that the ship may have been a Chinese junk. They further suggested that the junk sank as early as A.D. 1130. Although the latest copper coins they observed were from the Zhonghe period (with the final year being A.D. 1118), I have seen later coins—purportedly from this wreck—from the Jian Yian period (whose final year is A.D. 1130). Personally, I believe the wreck may date later than A.D. 1130, likely around A.D. 1150–1175; I will explain my reasoning below.

|

|

Additional Research and Findings

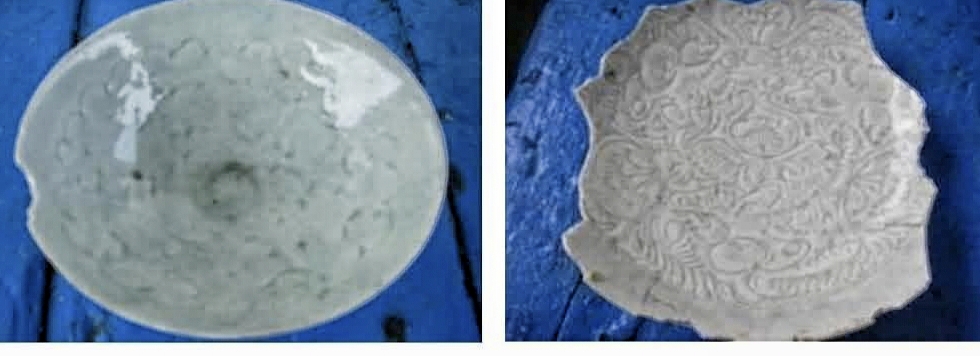

Subsequently, I encountered a paper by Jujun Kurniawan, who was involved in salvaging the Jepara wreck in 2007—by which time the wreck had already been largely looted. Nevertheless, a significant amount of information was recovered. As with some other 12th‑century wrecks, a small quantity of Jingdezhen qingbai wares was also present.

|

| Two Jingdezhen Qingbai bowl, one with carved absract waves and the other infants among foliage (Photo Credit: Jujun Kurniawan) |

Rise of Quanzhou Port and Fujian Trade Ceramics

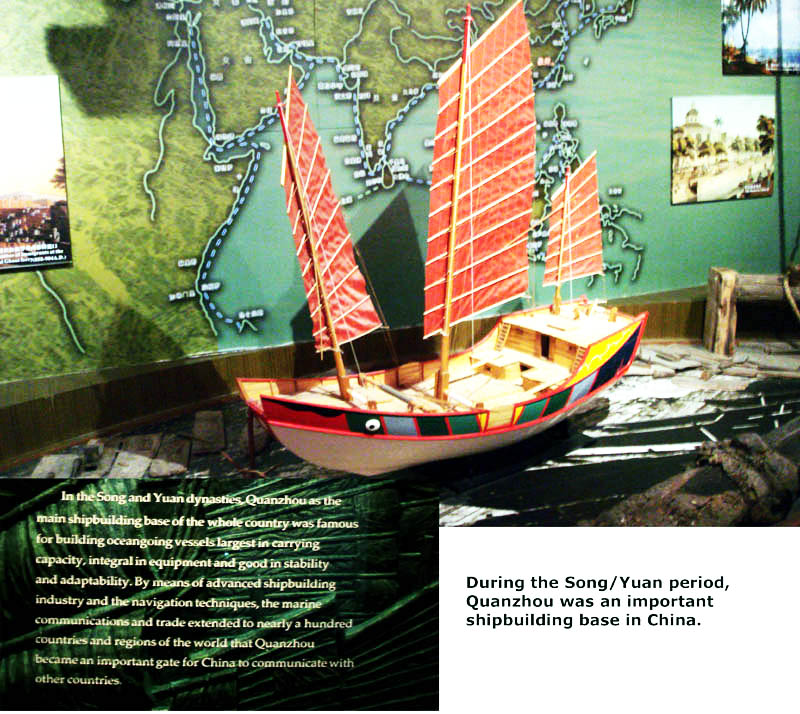

Quanzhou, located in Fujian Province, was a cosmopolitan port known to Marco Polo as Zayton and was the largest seaport in Asia during the Song and Yuan periods. Many regions—especially those along the Fujian coast—capitalized on their proximity to Quanzhou by producing export porcelains. The bulk of these trade ceramics comprised green wares (celadon), white (qingbai), and black/brown wares.

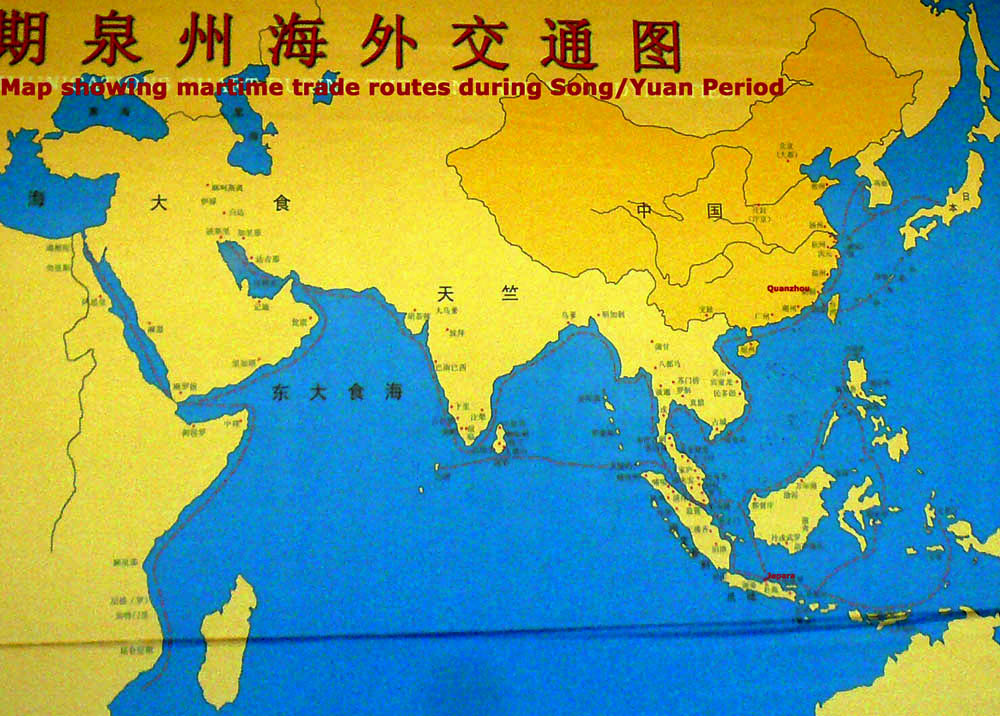

According to Zhao Rugua’s Song‑period work Zhufanzhi (c. A.D. 1225) (赵汝适《诸番志》), 46 countries—including Annam, Cambodia, Srivijaya, the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Java, the Eastern Indies, the Philippines, and even Zanzibar—were listed as China’s trading partners. The Yuan‑period work Daoyi Zhilue by Wang Dayan (汪大淵《岛夷志略》) lists at least 58 countries.

A map in the Quanzhou museum shows the maritime trade routes originating from Quanzhou. Although Jepara lies along one of these routes, it is unclear whether it was the intended destination of the ship that sank offshore.

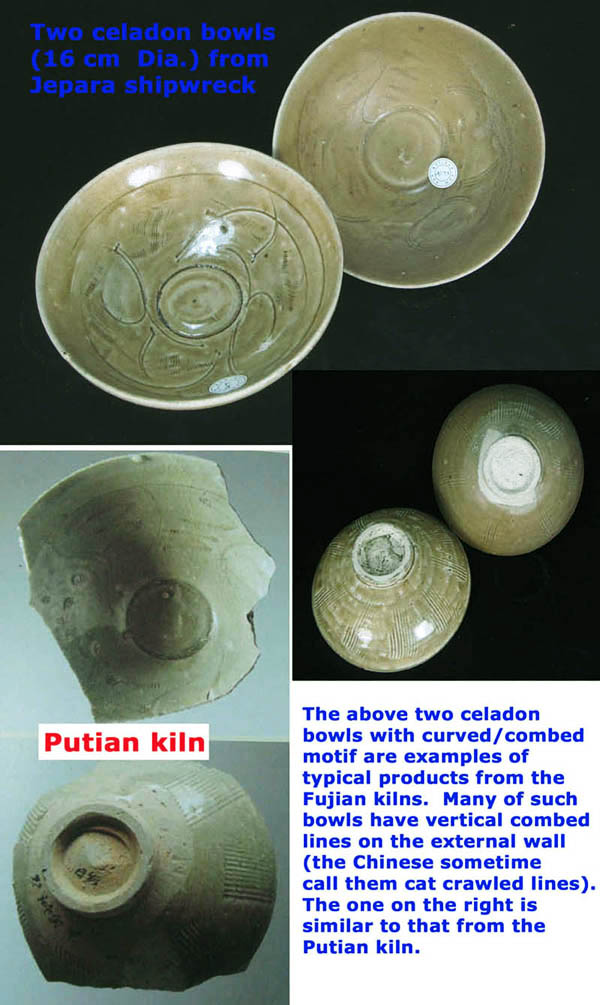

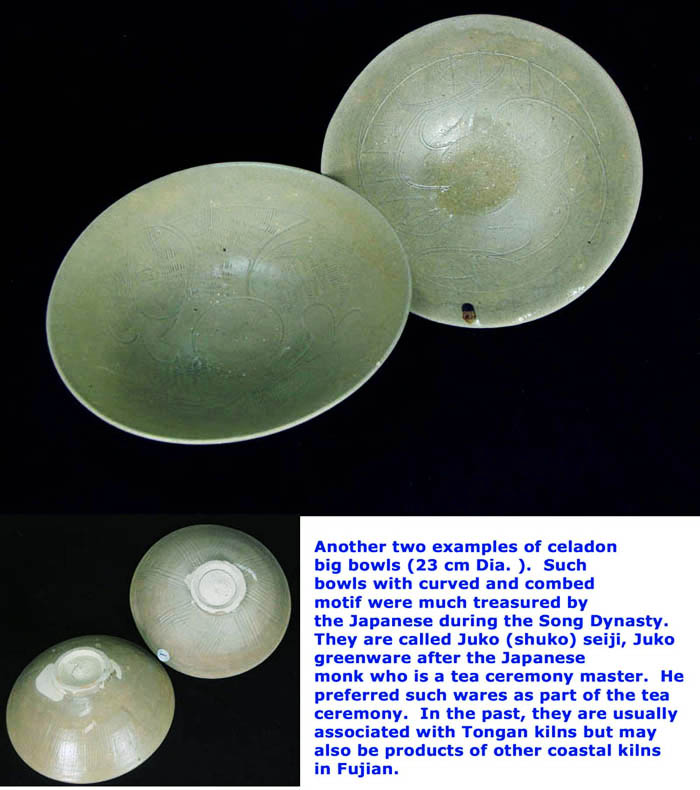

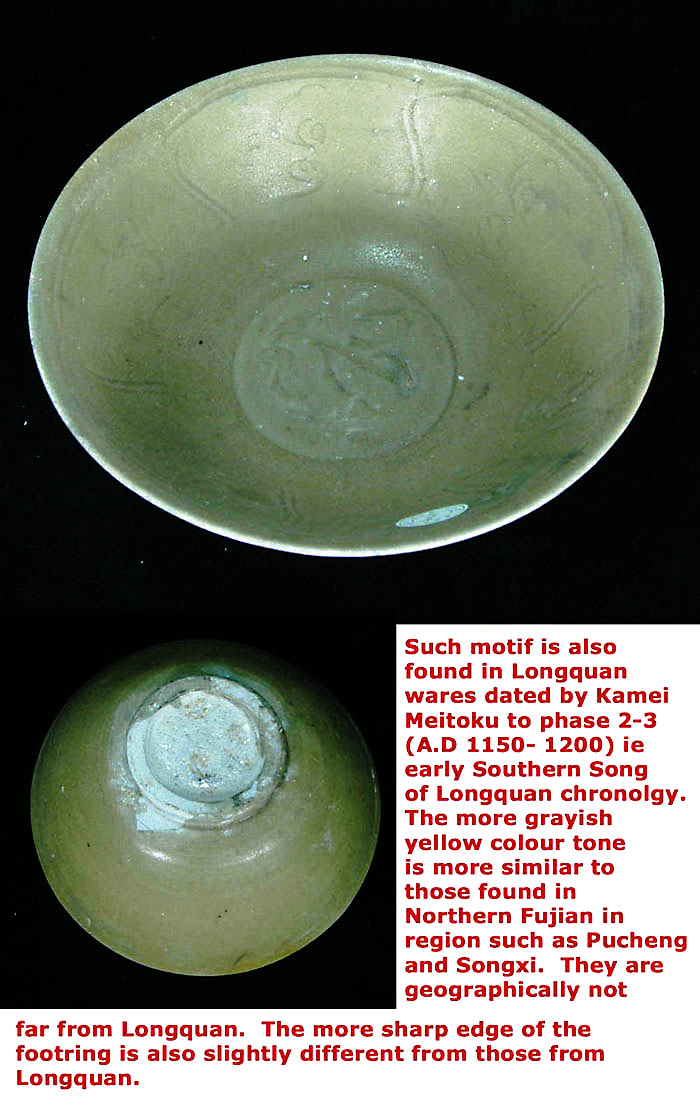

Ceramics in the Jepara Wreck

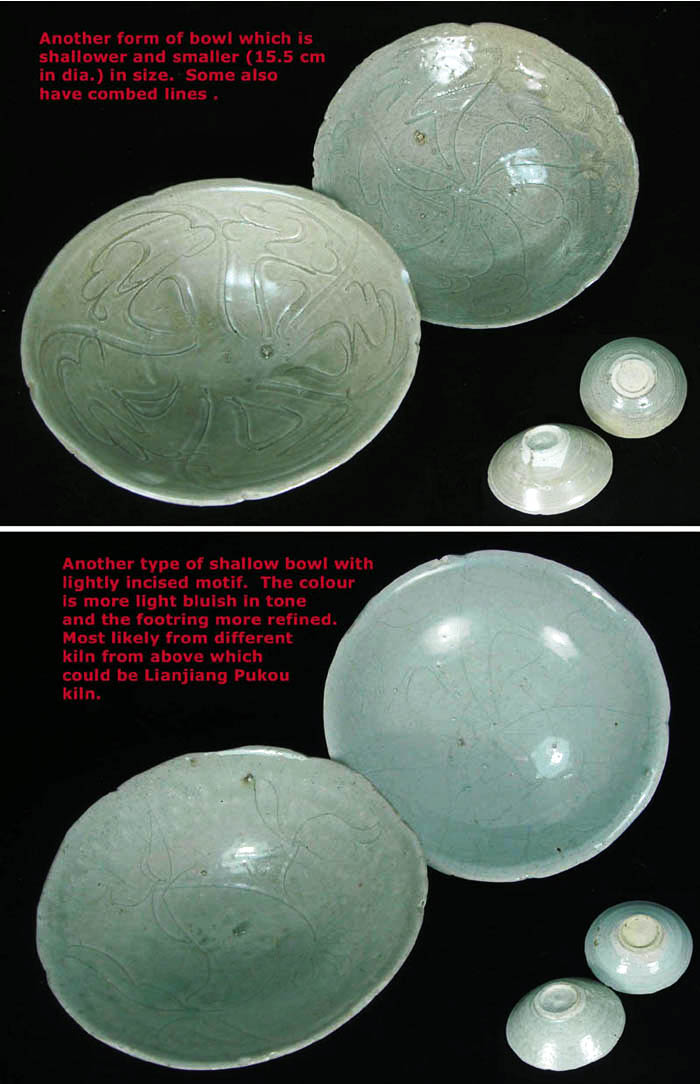

Among the wreck’s cargo are both large and small bowls featuring carved and combed or dotted decorations on the interior and vertical combed lines on the exterior. This style is commonly termed “Tongan type” or “Juko (shuko seiji)” greenware (named after Juko, a Japanese tea ceremony master) and represents a continuation of the Longquan tradition. Longquan kilns began producing such wares during the mid‑to‑late Northern Song period. In his article Chronology of Longquan Wares of the Song and Yuan Periods, Kamei Meitoku classifies these pieces as dating to the first half of the 12th century. However, the significant quantity found in the Huaguang Jiao 1 wreck—dated to around A.D. 1162 based on a green glaze bowl with the incised cyclical date “ren wu (壬午载潘三郎造)”—indicates that the Fujian version continued to be produced at least until around A.D. 1175.

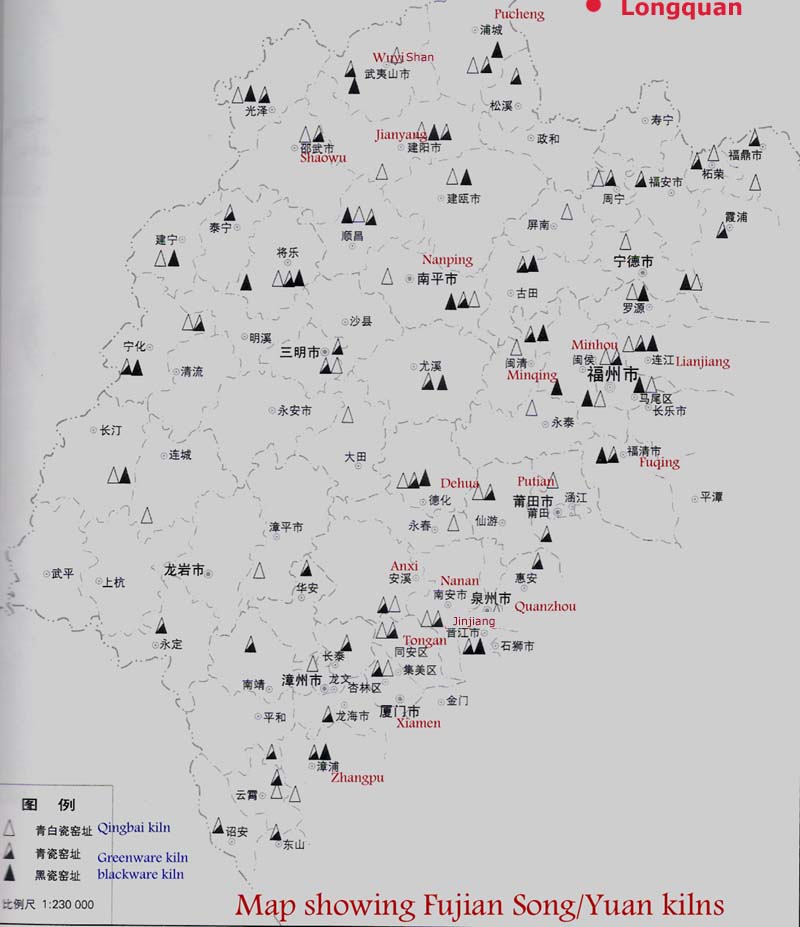

The center of production in southern Fujian was Nan’an (南安), which boasted more than 47 kilns. Together with nearby kilns such as Tong’an (同安), Anxi (安溪), and Xiamen (厦门), and others further afield (Minhou [闽侯], Fuqing [福清], Putian [莆田], and Lianjiang [连江]), these workshops produced similar green wares for the overseas market. (It should be noted, however, that kilns in northern Fujian also produced comparable wares.)

The color tones of these Fujian wares range from olive green to grayish green, with varying degrees of yellow. Compared with the Longquan version, the Fujian pieces are less refined; in most cases the outer lower portion of the bowls is left unglazed (whereas in the Longquan version only the outer base is unglazed).

|

| Example from the Huaguang Jiao 1 wreck featuring a Chinese “Ji” (吉) character—a product of a Fujian Tongan/Nan’an kiln. |

|

|

| Small green glaze bowl (diameter 12.5 cm) with an abstract carved decoration on the cavetto. Similar bowls have been found in the Huaguang Jiao 1 and Java Sea wrecks |

Fujian green glaze plates with carved floral decoration (Photo credit: Walter Kassela)

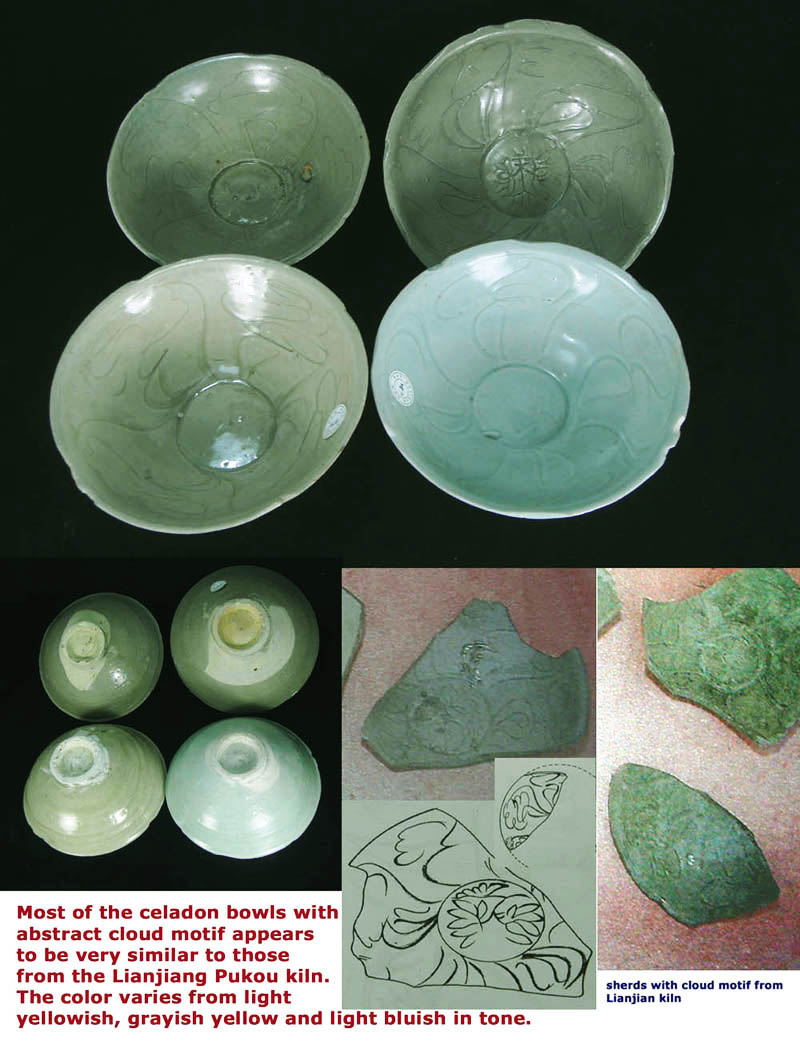

Fujian potters also introduced new decorative motifs. One popular design was the abstract cloud motif; based on archaeological findings, the Lianjiang Pukou kiln has been identified as a major production site.

There are also many celadon bowls with carved lotus motifs. This type was initially produced in Longquan kilns and later copied by Fujian potters; both versions are present in the wreck. Most Longquan and the majority of Fujian bowls do not feature vertical combed lines on the exterior. Kamei Meitoku dates the Longquan bowls to A.D. 1150–1200. In the Jepara wreck, however, some Fujian bowls display a sketchily carved lotus decoration with exterior carved lines. Whereas Longquan potters generally ceased decorating bowls with vertical combed lines by A.D. 1150, Fujian potters continued to use this technique for a couple of decades on some of their products.

|

|

|

| Longquan celadon bowl with carved lotus decoration. |

|

|

Large celadon bowls decorated with wild goose and floral scroll motifs. These have been attributed to the Anfu kiln in Longquan, as noted in the book “Ceramics from Tioman Island,” based on an archaeological report from China. |

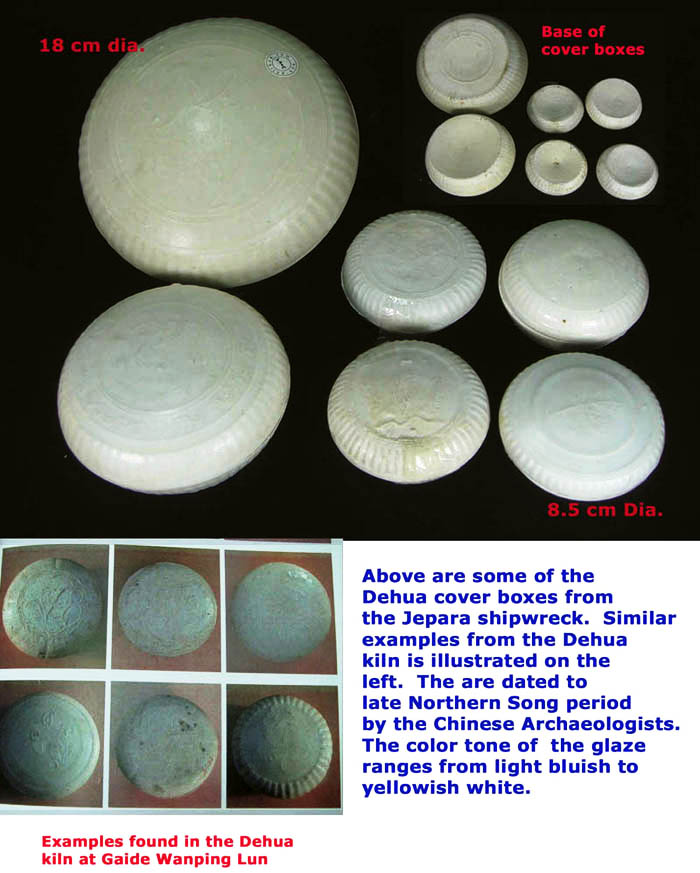

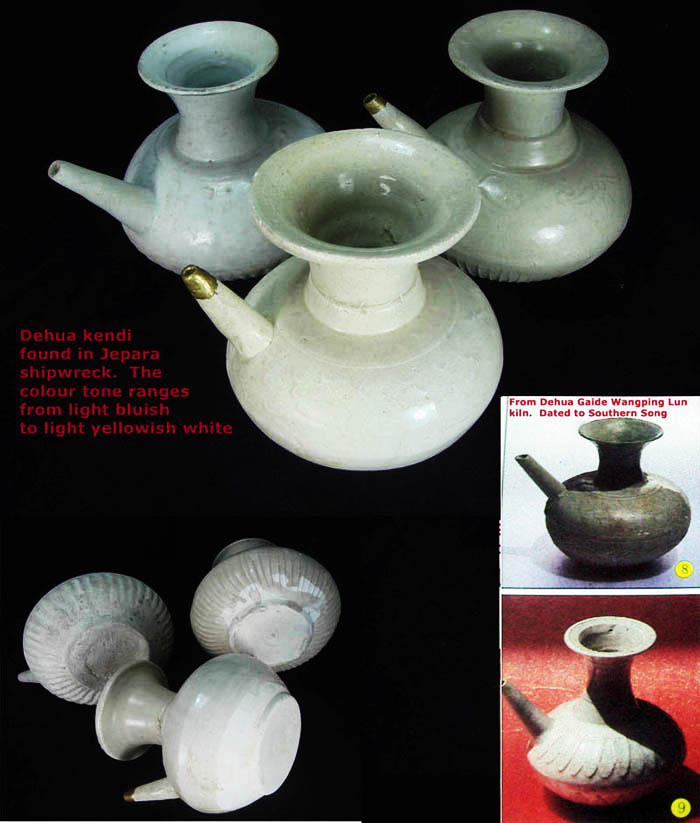

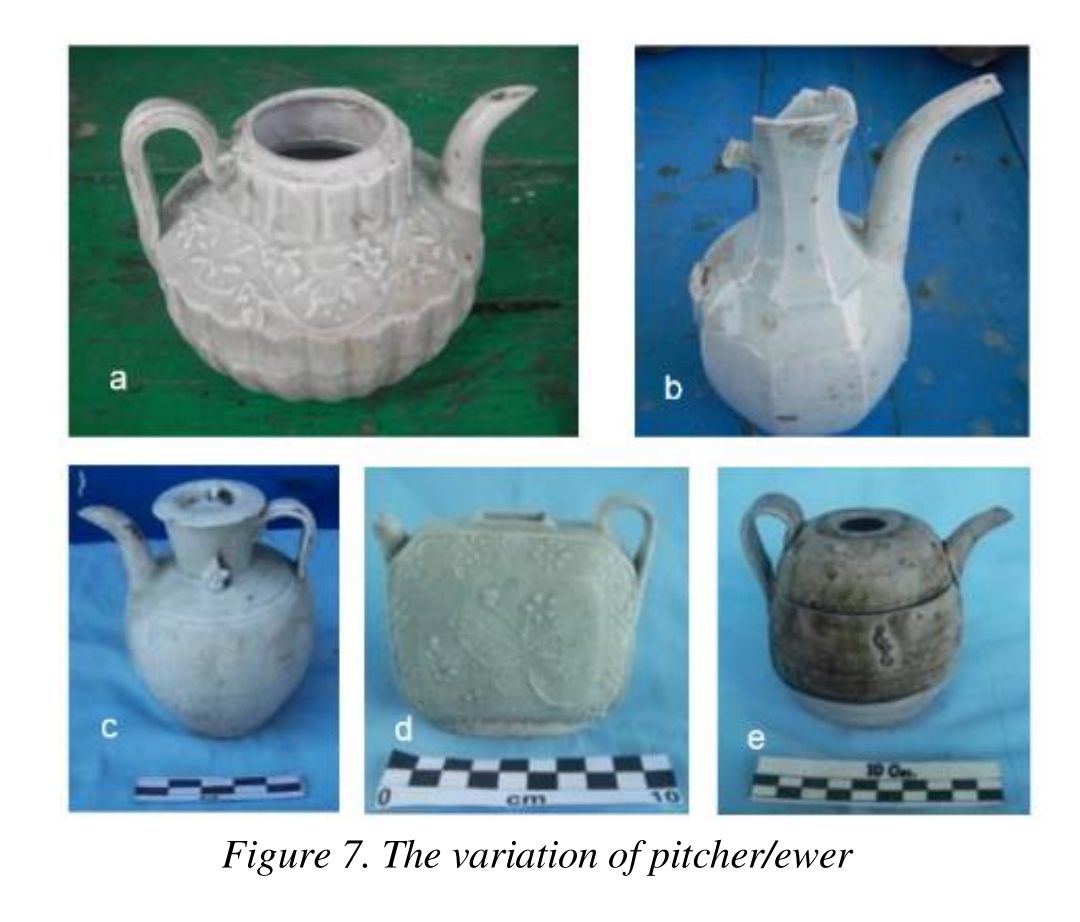

The Jepara wreck also carried a substantial quantity of white (qingbai) wares, including cover boxes, bowls, kendis, and vases. The majority of these pieces are likely products of the Dehua Wanpinglun (盖德碗坪崙) kiln, which Chinese archaeologists date to the late Northern Song period. A large number of cover boxes—varying in size and either plain or featuring impressed floral or abstract motifs—were recovered.

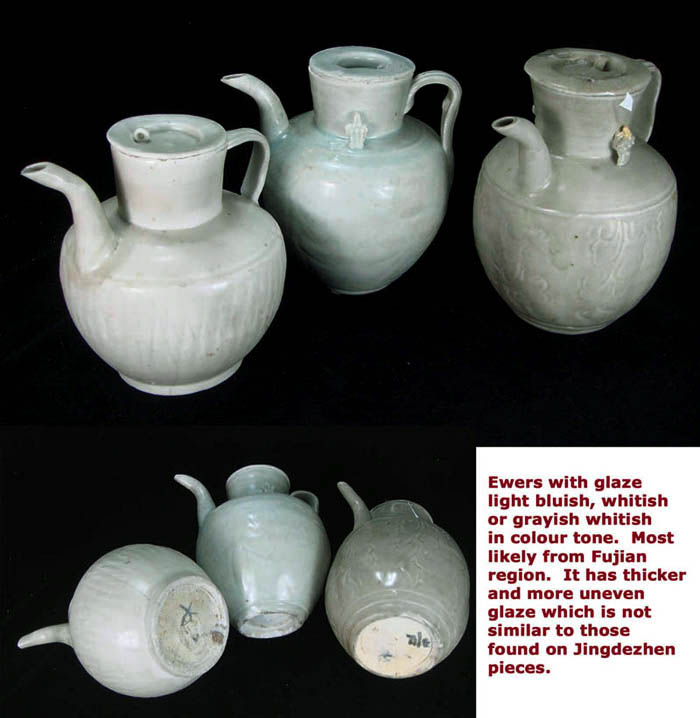

The wreck also included many large white glaze bowls from Dehua, either plain or decorated with abstract combed designs, as well as kendis with impressed floral and wave decorations. In addition to those with a creamy white glaze, some kendis exhibit a light bluish qingbai tone. Bottle‑shaped vases and a small number of floral‑shaped mouth vases with impressed floral decoration were also found, along with a group of white glaze jarlets.

T

|

| Elaborately decorated floral‑shaped mouth vase from the Dehua kiln (Photo credit: Walter Kassela). |

|

s

s |

| Dehua white glaze jarlet. |

|

| Qingbai wares such as ewers and bowls. Note that the ewers produced in southern Fujian bear a strong resemblance to those found in the Sabah Flying Fish wreck, dated to the closing years of the Northern Song period. They could be proudct |

|

|

|

Southern Fujian kiln qingbai bowl. Similar bowls have been found in Huaguang Jiao 1 and Java Sea wrecks.

|

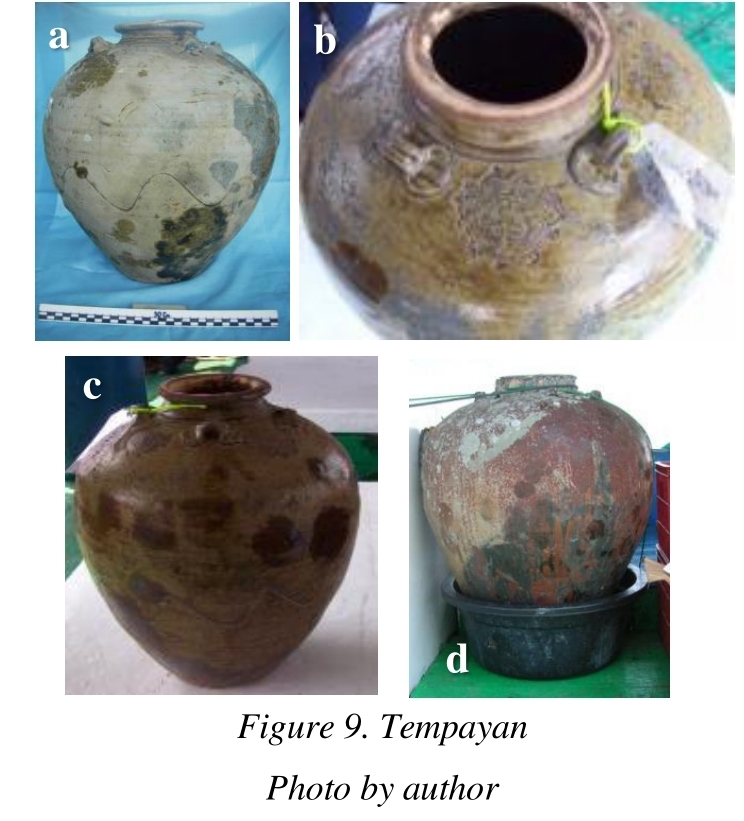

This category includes dark brown glaze kendis, jarlets, and celadon glaze kendis featuring iron‑brown painted abstract motifs. These pieces are most likely products of the Fujian Cizao kiln in Quanzhou.

|

|

| Fujian Cizao kiln brown glaze jarlet |

I

Dating of the Jepara Wreck

The presence of Jianyan copper coins indicates that the wreck dates to after A.D. 1130. Based on archaeological evidence, the Fujian and Longquan green glaze wares found can be dated to the A.D. 1150–1200 phase. The Dehua wares—likely from the Dehua Wanpinglun kiln—are dated by Chinese archaeologists to the late Northern Song period, with production possibly continuing into the early Southern Song period. Notably, the Dehua wares from the Huaguang Jiao 1 wreck (dated to A.D. 1162) are stylistically different from those in the Jepara wreck, suggesting that the latter could be earlier.

In Jujun Kurniawan’s article, an elongated octagonal qingbai ewer and several large brown Guangdong/Fujian jars were noted; these are similar to items found in the Huaguang Jiao 1 wreck (华光礁一号沉船). In Huaguang Jiao 1, a green glaze bowl with the incised cyclical date “ren wu (壬午载潘三郎造)” corresponds to A.D. 1162.

|

|

| The ewer (photo b) and the Guangdong Qishi kiln brown glaze jars from the Jepara wreck are similar to those found in the Huaguang Jiao 1 and Java Sea wrecks (Photo credit: Jujun Kurniawan). |

Taking these references into account, it is reasonable to conservatively date the Jepara wreck to around A.D. 1150–1175. However, additional evidence—such as the late Northern Song dating for the Flying Fish wreck and the Wanpinglun Dehua wares—suggests that the Jepara wreck may belong to the transitional phase between the Northern and Southern Song periods, possibly closer to A.D. 1150.

Written by: NK Koh

(20 Mar 2010; updated 20 Mar 2013 and 25 Apr 2023),

editced with ChatGPT on 7 Feb 2025.

References